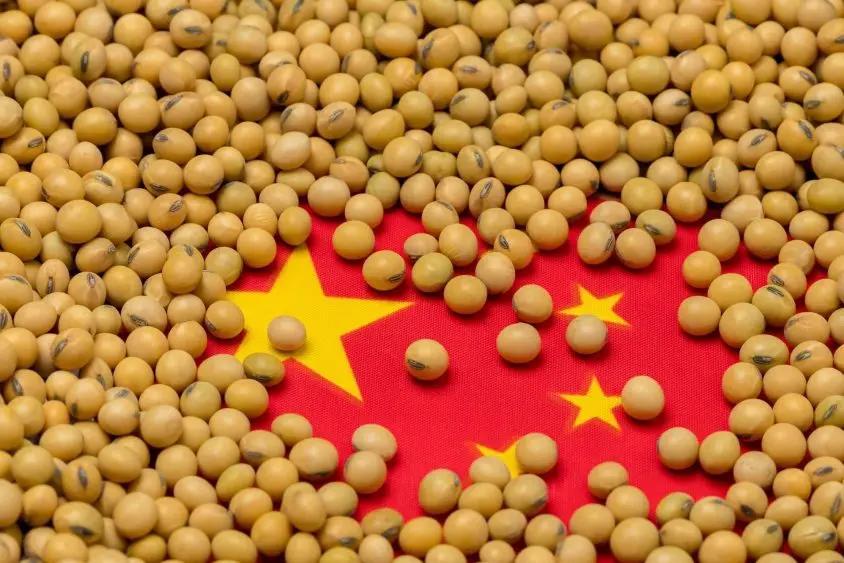

President Donald Trump said Tuesday he’s considering blocking imports of used cooking oil from China in response to the country cutting off all purchases of U.S. soybeans.

“I believe that China purposefully not buying our Soybeans, and causing difficulty for our Soybean Farmers, is an Economically Hostile Act,” Trump wrote on Truth Social Tuesday. “We are considering terminating business with China having to do with Cooking Oil, and other elements of Trade, as retribution.”

The president is referencing the commodity of used cooking oil. Used cooking oil (often shortened to UCO) is vegetable oil or animal fat that has already been used for cooking or frying food. After it’s used, instead of being thrown away, it can be collected, filtered, and processed for reuse—most commonly as a feedstock for renewable fuels.

The United States—a nation of plentiful restaurants, fast food joints, and deep-fried treats imports a waste commodity that’s domestically abundant. You’re not alone in raising an eyebrow at that fact, it’s an interesting trade practice.

Let’s start with the purpose of acquiring UCO. The United States imports large volumes of used cooking oil to make renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel. Because used cooking oil is a waste-based feedstock, it qualified for compliance credits under the Renewable Fuel Standard up until recently. Over the summer, Congress passed a major package of tax and clean energy reforms that tightened eligibility for the clean fuel production credit (45Z). Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” includes a provision disqualifying certain imported feedstocks—such as Chinese UCO and foreign tallow—from receiving U.S. clean fuel incentives. Now, regulatory agencies work to develop the legal framework to enforce these changes.

Imports surged beginning in 2021–2022 as U.S. renewable diesel capacity ramped up. China supplies roughly 60–70 percent of U.S. imports, helped by its large population and restaurant sector, lower collection costs, and established export logistics. It’s important to note China has drastically different labor laws than the U.S., allowing for low labor costs, which translates into a cheaper product. Refineries operated by companies such as Neste, Marathon, and Diamond Green Diesel lean on these readily available and cost-saving streams to keep units running.

On its face, the financial logic could be straightforward: imported UCO is plentiful, relatively cheap per gallon, and is integrated into efficient export supply chains. The economics favor imports in the short run. Shipping and landed costs for foreign UCO can keep delivered material in the neighborhood of roughly the low-$1s per gallon equivalent, while a new U.S. pre-treatment plant requires $10–$20 million for a 5–10 million gallon unit and $40–$80 million for a 50–100 million gallon unit, even if operating costs are only a few dimes per gallon once built.

Carbon is where domestic supply holds a clear advantage. UCO collected at home for renewable diesel commonly certifies at very low carbon intensities because trucks travel shorter distances and pre-treatment loads are modest. Meanwhile imported streams can score materially higher after ocean shipping and foreign energy mixes are included. As a simple illustration, replacing half of a recent record import year’s UCO volumes with domestic supply would reduce three-quarters of a million metric tons of CO₂ annually, even before considering any batches that might be misclassified abroad. Avoiding a single large trans-Pacific shipment can eliminate several thousand tons of CO₂ tied solely to freight.

While this seems like a no-brainer to farm country, some industry groups (notably parts of the refining/oil sector) push back, arguing that U.S. supply won’t suffice to meet mandated blending volumes without imports.

Its not that domestic collection isn’t occurring, many American firms already source and process domestic UCO. Darling Ingredients, through its DAR PRO network, collects restaurant grease nationwide and supplies Diamond Green Diesel. Chevron’s Renewable Energy Group operates plants that pre-treat and convert U.S. waste oils, including through SeQuential on the West Coast. Mahoney Environmental partners with national chains, and regional firms like Baker Commodities and others round out collection. The domestic system spans about 15 states with significant collection and pre-treatment capacity—Texas, Iowa, Illinois, California, Missouri, Minnesota, Louisiana, Oregon, Washington, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, and Nebraska—yet it is not large enough to meet the pace of renewable diesel expansion.

Could the U.S. find more supply at home? Potentially, but only with better infrastructure. Gaps persist in rural pickups, small-restaurant access, and institutional generators like schools, prisons, and military bases. Additional aggregation hubs, standardized pickup systems and containers, more pre-treatment capacity, and modern traceability tools could unlock significant volumes. Policy that specifically rewards U.S.-sourced waste oil—alongside grants or financing for new pre-treat units—would accelerate build-out. The biggest untapped opportunities sit in the Southeast; dense but under-captured urban corridors of the Midwest and Rust Belt; the Southwest and Mountain West where oil often travels long distances for cleaning; large institutional kitchens; and at major ports where cruise and shipping operations generate recoverable oil. With the right logistics and incentives, the United States could plausibly double or even triple current domestic recovery, reducing dependence on imports while supporting farm markets and local jobs.

Quality and processing details shape the debate. China generally cleans and dehydrates UCO before export to meet basic specifications, but what arrives is still a technical feedstock. U.S. refiners reprocess it—degumming, neutralizing, bleaching, and filtering—before hydrotreating. Domestic UCO often reaches processors cleaner and more consistent because it moves through shorter, regulated chains with direct contracts, which also simplifies audits. These differences in chain length and oversight underpin traceability and fraud concerns around some foreign cargoes.

Globally, there’s a growing body of evidence, reporting, and investigative pressure pointing to suspicions and alleged instances of fraud or adulteration in Chinese (and other Asian) UCO exports.

Transport & Environment’s briefing “Used Cooking Oil: The Certified Unknown” argues that chemically, waste cooking oil and refined virgin vegetable oils can be extremely similar, making lab tests only weakly diagnostic. Audit trails, documentation, and chain-of-custody are often the only reliable check. Because of that, the system relies heavily on paperwork audits rather than full lab confirmation, giving bad actors room to mislabel or mask origin.

Another Transport & Environment’s analysis shows that in many countries (especially in Asia), reported export volumes of UCO exceed credible collection estimates—suggesting some of the exported material must come from sources outside legitimate waste oil streams. Take into consideration Chinese SAF plants already absorb substantial volumes of UCO domestically—with 100,000 to 120,000 tons of UCO being used each month in China’s own biofuel / SAF productions.

The Transport & Environment report cites multiple cases in Europe where imported biodiesel or waste-oil-based fuels were reviewed and found to be based on mislabelled feedstocks. The same report notes that Europe historically identified hundreds of suspicious shipments from China, prompting tightened customs scrutiny and rejections of some imports.

While the evidence is not uniformly definitive, it’s strong enough to be taken seriously by U.S. regulators, senators, and biofuel companies.

In June 2024, a bipartisan group of farm-state senators sent a letter to the EPA, USDA, U.S. Trade Representative, and Customs, asking for stronger enforcement and transparency around rising UCO imports from China and other countries, citing fraud and mislabeling risks.

More recently, Senator Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) joined calls for the EPA to finalize rules on RINs for imported biofuels and to hold firm on biomass-based diesel volume mandates, with emphasis on protecting domestic agriculture. Senators have also urged the EPA to finalize the “Set 2” RFS rule with strong biomass-based diesel targets and provisions that favor domestic feedstocks.

Even as Congress and the agencies press reform, legal and practical challenges remain—for instance, refining complex rules distinguishing domestic vs. imported feedstocks without violating WTO or trade obligations.

Because domestic collection capacity and feedstock availability lag demand, overly aggressive restrictions on imports could strain supply or raise fuel costs. Enforcement of traceability rules for imports demands substantial audit, testing, and verification infrastructure, which is still evolving.

Continuing to import waste oils keeps renewable diesel and SAF capacity fully utilized at attractive short-run costs, but it perpetuates strategic dependence and traceability disputes. Investing to expand domestic collection and pre-treatment—especially across the Southeast, urban Midwest, and institutional generators—builds a cleaner, verifiable, home-grown feedstock base that supports the agricultural economy, reduces lifecycle emissions, and hardens the supply chain against geopolitical shocks. The technology is proven, the companies exist, the credit frameworks are in place, and the untapped supply is real. What remains is scaling domestic infrastructure to match America’s ambition in low-carbon fuels. Additional aggregation hubs, standardized containers and routing, more pre-treatment capacity, and modern traceability tools could unlock significant volumes. Policy that specifically rewards U.S.-sourced waste oil—alongside grants or financing for new pre-treat units—would accelerate that build-out.